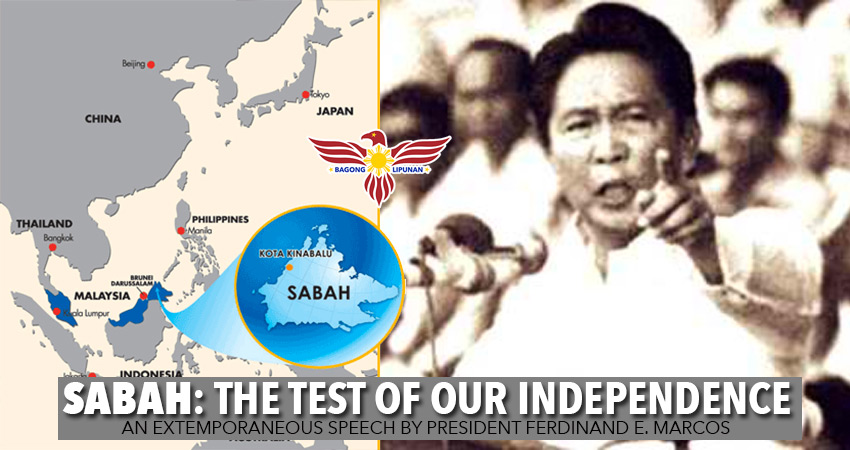

Sabah: The Test of our Independence (Speech of President Marcos)

On September 26, 1968, Former President Ferdinand E. Marcos (FEM) gave this Extemporaneous Speech at the Lions Convention in Dagupan City.

I am very happy to be here. I always enjoy coming to Dagupan and to Pangasinan. Your sense of humor, your pleasant habits and instincts inspire me into believing that if we have more people like you, we should have a more pleasant way of developing the country. I presume that there are also Liberals among you. I wish your habits would contaminate the Liberals that I know.

Mayor Manaois told me to enjoy myself here in Dagupan. How, he did not say. But I always enjoy his speeches. They are in a class completely different from all the speeches that I have heard. And after a gruelling period of work in Manila, I always look forward to listening to Mayor Manaois. But this time, he overdid himself. . . .

I have agreed to an open forum because whatever I say here will be further embroidered and probably made more interesting by direct confrontation with the leaders of your area. I always accept an invitation from District 301-C. You will remember I was with you on your last convention, and I was afraid then of being involved in the politics of your association, which is as intense and as bitter and as partisan as anything in the Philippines. But I was also with you during the campaign in 1965. I think my being with you now is the third time around. I hope this insures your support for me in whatever aspirations I may have in the future.

But all kidding aside, you come from the district to which most people refer as my bailiwick. Because Northern Luzon or Northern Philippines is the area which has given me the most number of votes in as solid a manner as any candidate has ever been supported in his entire political career. And you represent the leadership in this area, for whether you are in government or in private life, you constitute the leader class. And it is the leader class often that molds and forms opinions. For while it is true that we live in a democracy and that your vote or any vote from each and everyone of you is equal to the vote of the meanest and the lowest and the poorest of Filipinos anywhere in the Philippines, it is true too that tradition, history, as well as the very nature of democracy allow the exercise of both character and the faculties of the mind, which provide the lead for those who may not be capable of forming their own opinions, and to mold such opinions for the good or worse of our country and our people.

Yesterday, I passed the 1000th day of my administration. 1000 days have passed as if they were merely but a single day. And I took forward to . . . . Of course, I hope another 1000 days. Now let’s see, does that extend to 1969? Yes, I am afraid it does. But always that is the feeling of a President; I presume whether he seeks re-election or not. Four years is always too often a short period for the implementation of projects which are considered long-term projects.

For instance, the project for the control of floods here in Central Luzon, you can’t finish that in five years. Because you will have to go into the sources of water in the Cordilleras, in the Sierra Madre, which serve Nueva Ecija, Bulacan, and Pampanga. And yet one has to plan. For instance, again, one has to plan on the economic relations between the Philippines and Japan, the Philippines and the United States, the Philippines and the Benelux countries, the Philippines and the common market; one has to make the foundations of all these plans. And yet one may not be there when the plans are implemented. Suffice it to say that the leader, if he is a leader, must initiate the first step towards the right direction, for the leader is chosen in order that he shall assume this initiative. And more often than not, assuming the initiative is a thankless task.

One is often criticized for things that he may not have done or he may not be even planning to do. Today we are involved in tensions with Malaysia. And both on domestic and any foreign problem that we have, this is a problem which engages the minds, and the hearts, the emotions and the feelings, of all our people. You are witness to the lively discussions of the Sabah issue, and I thought I saw or felt some expression of, shall we say, the humor in the situation, by the way you have reacted to the statements of the would-be governor of Sabah, Mayor Manaois. I think he was a little mistaken when he said that I’m the only President of Sabah. This is one of the things that I want to put right. Because the belief is that I suddenly pressed our claim to Sabah without any historical and without any legal foundation. This is not true. Of course if you ask our people, they will say we are unanimous in this decision to pursue the claim to Sabah. And you ask them why, and their answer is, we believe in Marcos, we will follow Marcos. And I think that is the attitude, too, of Mayor Manaois. Perhaps because it is also likely due to the fact that he is one of my closest friends, and the fact that I have given this city about a million pesos in aid. And whispered to me, I have not asked anything from you, Mr. President, at this luncheon; I shall reserve it for my next visit to Malacañang. And knowing him, he will probably be there tomorrow.

But am I the only President that has identified the Philippines with Sabah? No. Am I the only head of a sovereign state that has made a claim to the Sabah? No. Have we taken steps before to acquire Sabah? Yes. The Sabah territory is historically and legally an area and a territory to which we have, from the beginning of the 18th century, laid claim and over which we maintain dominion and sovereignty.

According to Dr. Tregonning, the Sabah region or what is properly known as North Borneo was ceded by the Sultan of Brunei in 1704 to the Sultan of Sulu as a sort of a reward for the help of the Sultan of Sulu in suppressing a rebellion in North Borneo.

Let me read from the “Diario Español” of January 28, 1876, wherein it said, clearly that the Sultan of Sulu was “lord of all the part of Borneo between Quimanis Point in the island of Labuan itself, and the Bay of Santa Lucia that is to say, 150 leagues off the north coast of the said island of Borneo, recognized by all statemens, including the Dutch, who were the owners of the nearest possessions. The title of the Sultanate of Sulu over North Borneo was recognized by Spain, Great Britain, and other European powers through a series of treaties entered into in the 18th and the 19th centuries. I need not go into them now. There at least 10 to 20 documents in the possession of the Republic of the Philippines indicating that the Sultan of Sulu was recognized as the ruler and the sovereign over North Borneo.

On what do we base, therefore, our claim? We have based it primarily on this: that this area was leased to the two adventurers, Baron de Overbeck and Alfred Dent, one an Austrian citizen and the other an Englishman. And this lease was recognized as such, merely a lease. This lease continued because of the payment of 5000 Malaysian dollars annually. Up to now this amount this amount is still being deposited. If this land was not leased out by the Sultan of Sulu why is it that up to now the rent is being paid? And the heirs of the Sultan of Sulu, of course, are quarreling as to who should receive this rent.

Did Baron de Overbeck and Alfredo Dent acquire sovereignty over the territory? No, because they were not acquire sovereignty and dominion over territory like this.

The question that arises next is when the North Borneo or Sabah territory was transferred by the North Borneo Company to the British Government, what was transferred? Could the North Borneo Company transfer anything more than what it had acquired from the Sultanate of Sulu? No, because you cannot transfer what is not yours. Since the Baron de Overbeck and Alfred Dent did not have sovereignty, they could not transfer sovereignty to the British government of British North Borneo. This is confirmed by the statements of British officials. Let us go to the statement of the Minister of Foreign Affairs 01 the British government in 1881.

Lord Granville stated the following and I quote, “the British Crown assumes no dominion or sovereignty over the territories occupied by the British North Borneo Company, nor does it purport to grant to the Company any powers of government thereover. It merely confers upon the persons associated status and incidents a body corporate, and recognizes the grants of territory and the powers of government made and delegated by the Sultans in whom the sovereignty remains vested.”

The Americans recognized this, and in 1920, through Governor Frank Carpenter, also recognized the sovereignty of the Sultan of Sulu over North Borneo. There was an agreement. First, there was the Bates Agreement during the revolution confirmed by the Carpenter Agreement in 1920. This Carpenter Agreement was further confirmed in a statement by Governor Carpenter when he said and I quote:

“It is necessary that there be clearly of official record the fact that the termination of the temporal sovereignty of the Sultanate of Sulu within American territory, which is Sulu proper, is understood to be wholly without prejudice or effect as to the temporal sovereignty and ecclesiastical authority of the Sultanate beyond the territorial jurisdiction of the U. S. government, especially with reference to that portion of the island of Borneo which, as a dependency of the Sultanate of Sulu is understood to be held under lease by the Chartered Company which is known as the British North Borneo Company.” So both the British and the American governments recognized this territory as under the Sultan of Sulu.

In the conversations or negotiations conducted in 1963 we made the following summary of our claim to the British and I quote:

“To put it in capsule form: it is our legal position that the Sultanate of Sulu had been recognized by the United Kingdom as the sovereign ruler of North Borneo; that the aforesaid contract of 1878 whereby the Sultan of Sulu granted certain concessions and privileges to Overbeck and Dent in consideration of an annual tribute of 500 Malayan dollars was one of lease; that whatever be the characterization of the contract, Overbeck and Dent did not and could not in any event acquire, as they could not have acquired, under applicable rules of international law, sovereignty or dominion over North Borneo; that the British North Borneo Company did not acquire as in fact it was not authorized to acquire, sovereignty or dominion over the North Borneo territory; that the British Government consistently barred the British North Borneo Company from acquiring sovereignty or dominion over North Borneo by maintaining that the same resided in the Sultan of Sulu; that as a consequence, the British Crown, on the strength of the North Borneo Cession Order of 1946 did not and could not have acquired from the British North Borneo Company sovereignty or dominion over North Borneo, since the Company itself did not have such sovereignty; that the said Cession Order was a unilateral act which did not produce legal results in the form of a new title; and that the Sultanate of Sulu, which in 1957 publicly and formally repudiated the Cession Order and terminated the lease contract of 1878, continued to exist, in reference to North Borneo, until the Philippines, by virtue of the title it had acquired from the Sultanate—and this was the formal Deed of Cession signed by the Sultan of Sulu in favor of the Republic of the Philippines in 1962—became vested with sovereignty and dominion over North Borneo.”

Colonial Paradox

What we appear to have here, my countrymen, is a paradox of colonialism. At the time when we were still a colony of Spain, and then later of the United States, the sovereignty of the Sultan of Sulu over North Borneo, or Sabah, was recognized and accepted as a fact by both Great Britain and the United States of America.

But with our national independence, when we could claim at least what was ours, we are told that the sovereignty of the Sultan of Sulu—and in consequence, Philippine sovereignty over North Borneo—has ceased to exist. Why is this so?

And then I am made to understand further that we should not press this claim because the great nations are against this claim. Great Britain is against this claim, apparently the United States is against this claim Russia is against this claim. If this be the test of the validity of claims then I am afraid that small nations m this world have no chance whatsoever to claim what is rightfully theirs. I maintain that as a basic principle, claims to territories, claims to boundaries and borders, should be decided on their merits and on the rule of law not on the rule of power and the rule of force.

There was much ado about the presence of British naval units, 25 of them, British and Australians, passing through our territorial waters. And with it also came the passage. the fly-by over our territory of jet fighters of the British. It could not have been too much of a burden to us or an imposition upon us, a small country who seeks nothing but peace, were it not for the statement that this was a show of force.

What is the meaning of a show of force? A show of force by the British indicates that this was an attempt to coerce us, to follow the will and the intention or the decision of the British to declare Sabah as Malaysian territory. Accordingly, therefore, as your President, I filed a protest with the British Embassy against the misuse of our territorial waters. The British, the United States and other countries are our partners in the SEATO, and therefore it is my hope that there will be no more show of force against a friend and an ally. Was it necessary to coerce us with this show of force? To compel us into quitting our claim? I have always said that no amount of show of force, provided that we are in the right, will compel me to change this decision because it is a decision based on law. It is a decision which is supported by the people and by Congress, by the representatives of the people. I am unable to change such a decision because with this show of force came the demand that we repeal a piece of domestic legislation. Can, therefore, or should a show of force, be allowed to compel a sovereign nation like ours to change its own domestic legislation? If the answer is yes, then ladies and gentlemen, our world is back to the law of the jungle, with the rule of law abdicated. And, therefore, even if ours be a small nation, we must stand firm behind the rule of law, especially international law.

But are we pressing our claim in order to prejudice the will of the Sabahans? No. Our intention is, at the appropriate time, we shall allow the principle of self-determination to apply. Meaning that we will allow a referendum or a plebiscite, properly safeguarded in order that it will be correct, true, authentic and reflective of the will and choice of the Sabahans for the future. But before we can go into this, just as what has been done with respect to West Irian, there must be a proper period within which preparations will be made for a proper referendum. Before this can be done, the legal question must first be decided, preparatory to giving away territory. You must first find out whether you own the territory or you have dominion over the territory which you will give away Before, therefore, any political action can be undertaken the legal question of who has sovereignty and dominion over Sabah must first be decided.

And our position is this: we do not want war, we do not want tensions, we do not want crisis, but we do want our rights first to be adjudicated, and to be adjudicated by the proper tribunal.

When the three heads of state met in Manila, meaning the heads of state of Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines in 1962, they entered into an agreement about Sabah. The Philippines was going to recognize Malaysia as a federation and as a separate state on condition that this would not prejudice the claim of the Philippines over the Sabah area which the three heads of the nations agreed shall be settled in a peaceful way through negotiation, through judicial intervention, through conciliation, or any other peaceful means agreed upon by the people.

This is our position: we want a settlement of this case by peaceful means. We don’t want a cavalier rejection of our claim because that is not included among the means with which to settle such a claim. A party litigant cannot decide his own case, and yet that is exactly what has been done in the present case. There are two prejudiced parties, both claiming the same territory, and yet one of them rejects the other’s claim and says that is the final decision on this case. How can this be accepted as such? Even if merely as a matter of principle, and because we maintain that the rule of law supersedes that of power, and aggravated by the fact that there are apparent attempts to coerce us as a nation and as a people into supporting such a violation of international law, it is necessary that we maintain our dignity, our sovereignty, by insisting on a decision by the proper tribunal. From our point of view, the proper tribunal is the International Court of Justice. The International Court of Justice is composed of international jurists who can be considered as the most prestigious in the world. They will not side with anyone, they will decide the question on its merits. If I, a party litigant, am sure of my case and of my evidence, why should I be afraid of bringing this case to the International Court of Justice? This is the question that we have asked the Malaysians and they have not answered.

We are, as a nation pledged to peace. Our Constitution renounces war as an instrument of national policy. We adhere to the United Nations principle of deciding territorial disputes by peaceful means. We have signed the Manila Accord and the Joint Statements of the heads of states and therefore we insist upon the referral of this case to the International Court of Justice. We believe m the validity of our claim. We believe we have every evidence necessary to plead our case. Now, if the Malaysians believe in the same way that they are right, let the court decide.

I have called for a summit conference; I have said I am willing to meet the head of state of Malaysia anywhere, any time, on any subject. They have put up many obstacles; they said there must be a ministerial conference first, meaning at the level of the secretary of foreign affairs. I directed the secretary of foreign affairs, Secretary Ramos of Pangasinan, to meet with his counterpart, Tun Abdul Razak, the foreign minister of Malaysia. Immediately, we are told that Tun Abdul Razak will not go to the United Nations. In short, they are avoiding this issue. I, therefore, place the responsibility on the Malaysians. It’s up to them now; we have invited them. I have said I am willing to negotiate. I hope that they will negotiate, they ‘ are our brothers. We don’t mean to do ill to them, we don’t wish ill on the Malaysians, but certainly it is necessary that we decide the Sabah question before we go into any other problem between Malaysia and the Philippines.

Now, I conclude with the statement that I shall continue to hope that we will be able to settle this question without delay and in an atmosphere of amity and friendship. I do not expect any war because neither country—the Malaysians nor the Filipinos—are capable of waging war or invading Sabah. But, certainly, both are capable of causing incidents that may lead into graver hostilities. So, the earlier we terminate these tensions, the earlier we settle these misunderstandings, the better for both countries. Both sprang from the same Malayan stuff, both live in the same area, and are neighbors to each other.

Of course, you may want to know why this claim was filed by President Macapagal, and I will tell you. President Macapagal, when he filed the claim in 1962, said that Malaysia is a part of the mainland of China. Presumably, therefore, if the mainland of China should be overrun by communists, Malaysia will also be overrun by communists. If Sabah belongs to Malaysia, then this entire state would come under the control and the hands of the communists. If this should come about, and Sabah falls, into communist hands, we would have a communist territory within six miles of our southernmost border. It would be a threat to the security of the Philippines. This was the position of the Philippines, this was the position of President Macapagal and the security agencies when the claim was filed in 1962. I do not know whether anybody can say that the situation has changed in the years from 1962 to the present. I believe the situation remains the same.

For a young and small nation, we have never shirked from our responsibilities in the family of nations. The treaties we sign are national pledges, and we adhere to them even if subsequent events indicated that they may be disadvantageous to us. We never abrogate treaties for we believe that the life of treaties must be lived through, if we are to behave responsibly. Our allies could always count on us in any undertaking, in peace and in war. We heeded the summons to Korea, because we had agreed in advance to the principles of the United Nations. We have gone to Vietnam, because we believed that it was consistent with our commitments. Perhaps, naively, we always wed our deeds with our words. But we believe that the consistency between word and deed is an imperative necessity for international cooperation and understanding.

We cannot believe that insincerity is the principle of the modern diplomacy that will save the world from the flames of war.

Does this mean that the Philippines is a La Mancha, a Don Quixote among nations.

If peace is a windmill and world understanding an unreachable star, if the quest for peace anywhere is an impossible dream, then let us prepare for the nightmare that is to come upon us.

The Continuing Hope

But, I must commend to you the continuing hope of this government that our brother Malaysians may yet perceive that our times call for the highest statesmanship.

I commend to you the hope that, here, in this small section of the world, there are people and nations who know how to take the first step to international peace and brotherhood.

And to this hope—and prayer—I, with your consent, commit each and every Filipino.

Thank you and good day.

Source: National Library